Top

Education

Research

Prize

Membership

Publications

Presentations

IconZoo!

Japanese books

Japanese

E-mail me

Research Topics

Chimpanzee–leopard relationships

Mahale is a unique research site of eastern chimpanzees where there are quite a lot of sympatric leopards.The relationships between great apes and large carnivores are interesting in terms of considering how predation pressure might have affected human evolution. In a collaborative study with Nobuko Nakazawa et al., we found evidence that a Mahale chimpanzee was actually eaten by a leopard (Nakazawa et al., 2013). On the other hand, chimpanzees can deprive a kill of a leopard (Nakamura et al., 2019). Such findings suggest that leopards are potential predators to chimpanzees but at the same time may be competitors over meat.

Mahale is a unique research site of eastern chimpanzees where there are quite a lot of sympatric leopards.The relationships between great apes and large carnivores are interesting in terms of considering how predation pressure might have affected human evolution. In a collaborative study with Nobuko Nakazawa et al., we found evidence that a Mahale chimpanzee was actually eaten by a leopard (Nakazawa et al., 2013). On the other hand, chimpanzees can deprive a kill of a leopard (Nakamura et al., 2019). Such findings suggest that leopards are potential predators to chimpanzees but at the same time may be competitors over meat.

Social Scratch

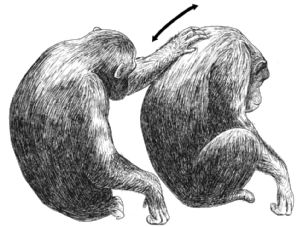

Chimpanzees of Mahale scratch other individuals' bodies while they groom them. This behavioral pattern of "social scratch (figure on the left)" is another example of social custom in chimpanzees, as it is not found in Gombe about 150 km north of Mahale, nor has it been reported from any other sites of chimpanzee study. Frequency of social scratch was correlated with frequency of social grooming, but not with frequency of self-scratch. Frequencies of social scratch per grooming bout among adult and adolescent males, and from lactating females to infants or juveniles, were high, and among males, higher-ranking males especially received more. These facts indicate some social function of the behavior. Social scratch was directed mostly to the dorsal side of the body. However, when lactating females social scratched to infants or juveniles, they scratched other body-parts. Social scratch was not lateralized to left or right. We present four hypotheses on the functional origin and on the learning process of this cultural behavioral pattern.

Chimpanzees of Mahale scratch other individuals' bodies while they groom them. This behavioral pattern of "social scratch (figure on the left)" is another example of social custom in chimpanzees, as it is not found in Gombe about 150 km north of Mahale, nor has it been reported from any other sites of chimpanzee study. Frequency of social scratch was correlated with frequency of social grooming, but not with frequency of self-scratch. Frequencies of social scratch per grooming bout among adult and adolescent males, and from lactating females to infants or juveniles, were high, and among males, higher-ranking males especially received more. These facts indicate some social function of the behavior. Social scratch was directed mostly to the dorsal side of the body. However, when lactating females social scratched to infants or juveniles, they scratched other body-parts. Social scratch was not lateralized to left or right. We present four hypotheses on the functional origin and on the learning process of this cultural behavioral pattern.(Nakamura et al. 2000)

Test on Dunbar's Efficiency of Language

Clique sizes for chimpanzee grooming and for human conversation are compared in order to test Robin Dunbar's hypothesis that human language is almost three times more efficient as a bonding mechanism than primate grooming. Recalculation of the Dunbar et al. (1995) data revealed that the average clique size of conversation was 2.72 while that of chimpanzee grooming was 2.18. The efficiency over "theoretical monkey" (who always grooms on a one-to-one basis and one-sidedly) was 1.27 in conversation and 1.25 in chimpanzees when we take role alternation into account. Chimpanzees can obtain about the same efficiency as conversation because their grooming is often mutual and polyadic.

(Nakamura 2000)

(Nakamura 2000)

Grooming Hand-Clasp

Grooming-hand-clasp (GHC) is one of the most well known social customs found among chimpanzee populations. I made detailed description of the behavior in Mahale M group. Sixty-five cases of GHC were observed in 1994, and 95 cases in 1996-1997. Twenty-four individuals in 28 different dyads participated in the behavior in 1994, and 20 individuals in 32 dyads in 1996-1997. The individuals with more cases of GHC tended to engage in more cases of BCG. However, dyads with more cases of GHC showed fewer cases of BCG, and vice versa. It is assumed that an individual differentiate these two by using either of them to a particular partner. There is a possibility that after they acquired GHC custom, chimpanzees inferred a different social meaning to it. This suggests that chimpanzees can, to some extent, culturally form their social behaviors.

Grooming-hand-clasp (GHC) is one of the most well known social customs found among chimpanzee populations. I made detailed description of the behavior in Mahale M group. Sixty-five cases of GHC were observed in 1994, and 95 cases in 1996-1997. Twenty-four individuals in 28 different dyads participated in the behavior in 1994, and 20 individuals in 32 dyads in 1996-1997. The individuals with more cases of GHC tended to engage in more cases of BCG. However, dyads with more cases of GHC showed fewer cases of BCG, and vice versa. It is assumed that an individual differentiate these two by using either of them to a particular partner. There is a possibility that after they acquired GHC custom, chimpanzees inferred a different social meaning to it. This suggests that chimpanzees can, to some extent, culturally form their social behaviors.(Nakamura 2002)

McGrew and others (2001) have reported that there are two different types of GHC: palm-to-palm and non-palm-to-palm. In the former type, two chimpanzees truly clasp each others‘ hands with mutual palmar contact, while in the latter, one or neither hand clasps the other, and usually the hands are flexed with one limb resting on the other. In their retrospective analysis of photographs and videos, they argued that palm-to-palm dominated in K group while the pattern was not observed in M group. We analyzed 100 photographs of GHC by the K and the M groups in order to test their hypothesis and found that palm-to-palm was also present in the M group. Interestingly, palm-to-palm was only performed when one of the females immigrated fom K group was involved.

(Nakamura and Uehara 2004)

Gathering of Grooming

Chimpanzees often groom in gatherings that cannot simply be divided into unilateral dyadic grooming interactions. This feature of grooming is studied at two different levels: grooming cliques and grooming clusters. Grooming cliques are defined as directly connected configurations of grooming interactions at any given moment, and when any member of a clique successively grooms any member of another clique within 5min and within a distance of 3m, all the members of both cliques are defined as being in the same grooming cluster. Twenty-seven types of cliques are observed, with the largest one consisting of seven individuals. Mutual and/or polyadic cliques account for more than 25% of all cliques. The size of grooming clusters varies from two to 23 individuals, and almost 70% of the grooming time is spent in polyadic clusters. Although adult males groom the longest in relatively smaller clusters (size=2-4), adult females groomed the longest in clusters of five or more individuals. A review of the literature implies that mutual and polyadic cliques occur less often in other primate species than in chimpanzees. The importance of overlapping interactions for these kinds of gatherings and its possible significance in the evolution of sociality is discussed in this article.

Chimpanzees often groom in gatherings that cannot simply be divided into unilateral dyadic grooming interactions. This feature of grooming is studied at two different levels: grooming cliques and grooming clusters. Grooming cliques are defined as directly connected configurations of grooming interactions at any given moment, and when any member of a clique successively grooms any member of another clique within 5min and within a distance of 3m, all the members of both cliques are defined as being in the same grooming cluster. Twenty-seven types of cliques are observed, with the largest one consisting of seven individuals. Mutual and/or polyadic cliques account for more than 25% of all cliques. The size of grooming clusters varies from two to 23 individuals, and almost 70% of the grooming time is spent in polyadic clusters. Although adult males groom the longest in relatively smaller clusters (size=2-4), adult females groomed the longest in clusters of five or more individuals. A review of the literature implies that mutual and polyadic cliques occur less often in other primate species than in chimpanzees. The importance of overlapping interactions for these kinds of gatherings and its possible significance in the evolution of sociality is discussed in this article.(Nakamura 2003)

Subtle Behavioral Variation

Complex feeding skills have often formed the central topic in the current studies of animal culture. In order to provide evidence that more subtle behavioral variations exist among wild chimpanzee populations, we directly compared the behaviors of two well-habituated chimpanzee groups, at Bossou and Mahale. During a 2-month stay at Bossou, I saw several behavioral patterns that were absent or rare at Mahale. Two of them, "mutual genital touch" and "heel tap" were probably customary for mature females and for mature males, respectively. "Index to palm (figure on the right)" and "sputter" are still open to question. These subtle patterns occurred more often than tool use during the study period, suggesting that rarity is not the main reason for their being ignored. Unlike tool use, some cultural behavioral patterns do not seem to require complex skills or intellectual processes, and sometimes it is hard to explain the existence of such behaviors only in terms of function.

Complex feeding skills have often formed the central topic in the current studies of animal culture. In order to provide evidence that more subtle behavioral variations exist among wild chimpanzee populations, we directly compared the behaviors of two well-habituated chimpanzee groups, at Bossou and Mahale. During a 2-month stay at Bossou, I saw several behavioral patterns that were absent or rare at Mahale. Two of them, "mutual genital touch" and "heel tap" were probably customary for mature females and for mature males, respectively. "Index to palm (figure on the right)" and "sputter" are still open to question. These subtle patterns occurred more often than tool use during the study period, suggesting that rarity is not the main reason for their being ignored. Unlike tool use, some cultural behavioral patterns do not seem to require complex skills or intellectual processes, and sometimes it is hard to explain the existence of such behaviors only in terms of function.(Nakamura and Nishida 2006)

Extensive Survey

I have also made several extensive survey in and around Mahale.

The photo shows Lubugwe River in the southern part of Mahale.

(Nakamura & Fukuda, 1999; Nakamura et al., 2005)

Study of Mahale Y group

Since 2005, Dr. Tetsuya Sakamaki and I have started habituation and the research on Y group that is adjecent group to well-studied M group. One purpose for this habituation is to reduce the concentration of researchers and tourists to the M group but in the long run we hope to understand the behavioral differences between two adjescent groups, relationships between the groups, transfer of the females and etc.